Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015) and Othering in Post-9/11 Horror

Six weeks after 9/11, Massachusetts’

governor forced me to resign. I was later sued personally for wrongful death by

a 9/11 family […] For many years, I feared that the blame was deserved. I was

broken by being blamed for the hijackings. Not instantly, but over time.

As

head of Logan Airport, I was blamed for 9/11 — and nearly broken by it. NYP: May 16th, 2020

In colonial New England, a young

woman, the eldest child who demonstrates individuality of her own, is

responsible for the care of her infant brother, Samuel. Whilst ‘peekaboo’, Samuel

abruptly vanishes, revealing to have been murdered by menacing forces that

cannot be located. Arguably, the shocking death of the baby analogises the

horrifying nature of the attacks in how they were unforeseen and involved an

innocent as their victim. Moreover, it leads to paranoia in attempts to unravel

the cause of what they understand as an assault by Satanic forces. In the

aftermath, a family’s suspicions and blames fall regularly upon the daughter, leading

to further disarray within the unit, something that Buckingham professed,

“Pointing the finger at convenient scapegoats won’t do a thing to address the

real issues confronting us” (May 16, 2020).

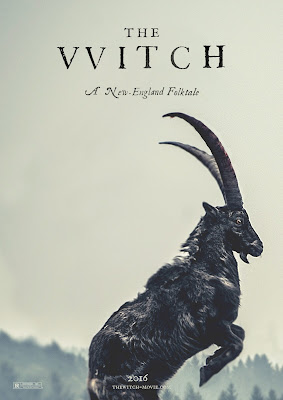

The folk horror film, The Witch

(Robert Eggers, 2015), is about scapegoating in a time of dread and hysteria in

the wake of a tragedy. In this article, I argue the film merits recognition as

an essential product of post-9/11 horror by comparing its characters and themes

with fearful reactions adopted in the wake of the attacks. A variety of

scholars amass that horror saw a significant revival after the September 11th

attacks (Kerner, 2015; McCollum, 2017; Pollard, 2011; Wetmore, 2012). The genre

stands out because, whereas “the heroic, dramatic and action genres fail to

present 9/11 in a manner that captures the experience”, horror would “step in

and embrace the fear of the events, not the heroism” (Wetmore: 2). Amidst this

distribution, McCollum, who wrote about the output of the often-termed folk

horror sub-genre after 2001 (2017), noted that “[these] films surface[d] to

interrogate the dynamic of state fear and political repression in a post-9/11

era rooted in urban terror” (2). She continues:

“[this] rural subcategory of

contemporary American horror cinema can be predominately characterised by its

exaggeration of anxieties arising from the intense resurgence of right-wing

populism and the decline of US democracy in the post-9/11 era.”

2017:

2-3

Kristen Moana Thompson argued that

the American horror genre’s administrative manifestation of dread in their

narratives indicates a historic blend of providential and messianic elements in

Puritan Calvinism along with deep-seated anxieties about historical

fragmentation and change (2007: 1-2). These are, she adds, exasperated onto

each film’s particular ‘monster’, whether this monster be physical or

hyperbolic (3). She added that “since 9/11, dread and fear have regained

prominence in the public sphere and become politically instrumental tools for a

messianic Bush administration” (17). In other words, whilst there was certainly

enough cause for fear, the issue is that the threat is purely internal and

manipulative. In this article, the author highlights The Witch in its

confrontation of both the Puritan messianic elements and the post-9/11 reaction

in its narrative of dread.

Considering Thompson’s above disclosure,

the film makes clear that it is not a monster but the Christian “patriarchal

structures that decry witchcraft that inevitably foreclose the options of the lead

character, Thomasin” that acts as the antagonist (Zwissler, 2018: 3). Writer/director

Robert Eggers personally expressed “desire to faithfully recreate both the

material conditions and the religious cosmology of colonial New England, a

worldview that contained monsters in the form of witches” (The A.V. Club,

2016). Therefore, the article will incorporate historic constructs of the witch

image primarily converging on Europe and America, as that is the film’s

setting, to highlight its principal argument.

How this aligns post-9/11 milieu is, the

attacks triggered Americans to return to these myths that have been ingrained

into our psyche and try to restore traditional gender roles out of fear. As

argued by Susan Faludi in her seminal novel (2007), ‘women’s independence was

implicated in the nation’s failure to protect itself’ (20). The main body is an

exploration of the power of dread and paranoia in horror through a contextual

and qualitative analysis of post-9/11 reactions. These are primarily the

reactions that disenfranchised women as the fault of the attacks, aligning it

with the representations of paranoia in misogynistic sentiment in The Witch.

Because the film is set in New England, the author will incorporate the

narratives the contemporary society accepted toward women; that being the

captive narratives and the witch stereotype.

The film continuously diverts from

what constitutes this stereotype through even its title. True, witches do

linger, yet their presence is sparse. Eggers allows the witch to be

interpreted, without pinpointing who or what is ‘the witch’. The Witch, as a

symbol, has recently been reconsidered in academic and popular thought as a

model of female power within cultural contexts harbouring underlying disquiet

with ‘women’ (see Roper, 2012). Chloe

Buckley states that “cinematic representations of the female witch have their

origins in classical mythology, the folklore surrounding the witch trials of

the Early Modern period” (2019: 22). Ronald Hutton concurs that the witch is a

‘cannibalistic, murderous and satanic’ figure associated generally with ‘evil

forces and antisocial attitudes’ (2017: 21). Hutton’s scrutiny of the earliest

witch trials (1426 -1448) reveals the most common traits that make up the

stereotype: the theft and murder of infants (170) as well as general isolation

in dark, haunting areas from society. We see these traits in The Witch, the film, with the

witches of the woodland that consume Samuel to gain their flight.

However,

as Buckley adds, “Horror cinema can also subvert older ideas about witches

and attempts to determine whether such representations underwrite or

undermine patriarchal values and constructions” (22). Eggers’ horror film is,

as Simon Abrahams stated in his contemporary review, a “feminist narrative” and

the “patriarchal stresses that lead to [women’s] disenfranchisement”, adding

that “all roads lead to Thomasin,” (2016). It is an insight into paranoia

aligned with misogynistic tendencies instigated by the adopted narratives

concerning women as witches when unexplainable ongoings occurred.

The infamous Salem trials, occurring in essentially the same era and area as The Witch (Massachusetts), are pinpointed as the most infamous ongoings of early modern Europe. Eighty per cent of the people tried were women and the criminal profile itself was heavily skewed to fit women as it was often sexualized, as in the pact sealed with demonic sex portrayed in The Witch. If we account for these findings collectively, we transition across the ages to note that the ideologies of the trial procedures equate with the media outlook on women on women today. Twentieth-century feminist studies congregated that the “representation of women reflected male attitudes and constituted misrepresentations of ‘real’ women” (Barker and Jane, 2016: 378). Diana Meehan examined women’s general roles on US television and a lack of power within those roles, or, more preferably, stereotypes (1983: 131). She suggested that the representations of women cast ‘good’ women as submissive and domesticated whilst ‘bad’ women are rebellious, independent, and ‘selfish’ (378). She christens this as none other than the ‘witch’, one with ‘extra power and subordinate to men’ (379). Although hailing from the 1980s, Meehan’s findings are endearingly relevant to the issues of post-9/11 medium this article aims to classify. Faludi asserts how, out of “all the peculiar responses our culture manifested to 9/11,” nothing “was more incongruous than the desire to rein in a liberated female population.” (2007: 20-1). In the next section, the article shall observe how the two stereotypes – ‘domesticated good wife’ and ‘rebellious bad wife’ – were not only reinstated but radically embraced after 2001.

On the day following the attacks, an assertion from Baptist pastor and conservative activist, Jerry Falwell, was released live on US television:

“[A]n angry God had allowed the

terrorists to succeed in their deadly mission because [of the] pagans, the

abortionists, the feminists and the gays […] who are actively trying to make an

alternative lifestyle.”

Laurie Goodstein, New York Times. Wed

19 Sep 2001

Although White House spokesman, Ken Lisaius, released a statement that “the president believes that terrorists were responsible” and “does not share [Fawell’s] views”, it seems that the pastor’s rhetoric “would be taken up by conservative pundits and in mainstream outlets” (Faludi, 2007: 22). Specifically, there was a significant drop in female representation on television and newspapers right after 9/11 by 40% (35-6) as well as most publicized stories in the weeks following the attacks featured men as gallant rescuers whilst women became surplus. The only narratives that placed women in the foreground were those focused solely on their role as mothers and wives as stories of pregnant widows whose babies were to be born after the death of their fathers were the favoured selection for newspaper covers. For Faludi, the “need to remedy that [America’s] failure somehow required a discounting of female opinions and a general shrinking of female profile” (21).

Uncannily, this ruminates the attitude Thomasin’s family adopt toward her, in how they quell her notable independence. From the prologue alone, the eldest daughter appears to or at least yearns to, begrudge the influence of her father, William (Ralph Inesin) on the unit (Bacon, 2019; Fry, 2019). As the family leave the plantation William had disputed with, nimbly following him, Thomasin visibly hesitates. She appears capable in leadership roles in the family as her mother grieves for Samuel. Yet, across the film, she is reprimanded by that family through her palpable assertiveness and attempts to be silenced and domesticated. Her parents contemplate that Thomasin should be married and sold off to serve another family, reminiscent of Faludi’s findings that the domesticated type was to be kept alive whilst the rebellious type is to be quelled.

If we dissect the derogatory remarks

of Falwell, we will notice that Thomasin matches all groups he names in his

rampage. Visibly, the feminist element has been established, but let us

overview the abortionist aspect. The way Eggers has her in the infant’s care

before his abduction invokes the above attack on abortion. Thomasin’s loss of

Samuel can be interpreted as a rejection of motherhood and instigating one of

the common stereotypes of witches: the theft and murder of infants (Hutton,

2017: 170-1). Moreover, the historical prelude to 9/11 shows that women’s roles

in the workforce both increased significantly. In the discourse of the women’s

rights movement, the birth control pill became significant. It gave women more

control over their bodies and freedom of choice over when/whether to have

children (Asbell, 1995: 104). Before the pill (pre-1970s), employees typically

had a 22-year-old child at work in their 40s. By the 70s, however, age rates

decreased to 13 or 14 and family dynamics were accordingly changed as the pill

allowed women control over their lives (Grunwald & Adler, 2005: 624).

Faludi (1999) describes the following

generations since the Second World War as the ‘promise of post-war manhood’ and

an eventual ‘betrayal’; that is, the “loss of the unstated covenant that men

had presumed gave them a valued place in the social order” (Barker and Jane,

2016: 377). The baby-boomer generation offered a ‘mission to manhood’ that

revolved around the conquest of space, the defeat of communism and a family to

provide for. Yet factors such as increased female presence in the workplace,

along with unemployment (by the onset of recessions) and the rise of feminism

all fit her series of documenting ‘men in trouble’ across the contemporary

American landscape (337-8). The patriarchal William can be viewed as a symbol

of ‘fragile masculinity. He is proven unable to either farm or hunt to keep his

family well-fed and the repetitive chopping of logs comes across as little more

than a display of his impressive physique.

As for the other type (the rebellious woman), Faludi exposes how “the few feminist pundits that managed to find a forum in this cacophony received a less than congenial” (27). Susan Sontag’s inflammatory article for The New Yorker (Sept. 24, 2001) suggested that the attacks were a response to the controversial and problematic US foreign policies, instantly warranted her with a panoply of insults. Magazine editors and columnists called her “deranged” and “an ally of evil”, and accused her of suffering from “moral idiocy” and of “hating America and the West and freedom and democratic goodness” (Faludi, 2007: 27). Toward the end of the film, when William, who believes her to be the witch behind their supernatural griefs, tells Thomasin that God will spare her if she admits the ‘truth’. Defiantly, she berates her father, calling him weak and hypocritical. This defiance is kerbed as William, unsure of how to comprehend the situation, locks his daughter in the goat house, ironically with the family goat, Black Philip, who is later revealed to be Lucifer. What this article will now highlight is something dissected by Susan Faludi as a history of American society reliant on what she designates as ‘captivity narratives’. As part of her exploration, she states that:

[T]he spectre of the white maiden

taken against her will by dark ‘savages’ became our recurring trope, riveting

the American imagination from Jane McCrea’s Revolutionary-era seizure and death

at the hands of British-allied Algonquins to the fictional Alice and Cora

Munro’s Indian immurement in The Last of the Mohicans to patty Hearst’s

kidnapping (and alleged rape) by members of the Symbionese Liberation Army

helmed by escaped black convict ‘Field Marshall Cinque’.

The

Terror Dream, 2007:

212

Ultimately, these narratives concocted symbols of the ‘devilish savages’ kidnapping and/or influencing the helpless female. Among the aforementioned anti-non-white, Christian category captivity narratives, a subgenre is the ‘Satanic Ritual Abuse’ story. In this type of narrative, a person claims to have developed a new awareness of previously unreported ritual abuse as a result of some form of therapy which purports to recover repressed memories, often using suggestive techniques. William’s credence that his daughter is a witch comes with the thought that she has been influenced by the Devil, apprehended like those in the stories cited by Faludi above. When Thomasin is defiant in his accusations, she is then declared equal to the Devil, scapegoated as an enemy of his dominant beliefs and thus confined with Him.

The presence of Black Philip, and therefore the witches of the wood, also appear a problematic presence for the Christian man. Though they are not direct symbols, they can be associated with discriminatory rhetoric toward Muslims after 9/11. This led to headlines such as “Islam and Freedom: Are They Destined to Clash?” or “Burka Makes Women Prisoners”, portraying those, similar to the feminist pundits that dared to repel the accepted narratives, as those “troubling the values of individualism and freedom said to define Western nations” (Morey & Yaqin, 2011: 1). It seems no coincidence that, through a mise-en-scene standpoint, Eggers has Thomasin and Black Philip confined together. Rhona Berenstein itemised that the aligning of a woman character with the monster of a horror film (using Aliens (1986) for analysis) invokes underlying empowerment whilst also beckoning patriarchal anxieties about this female power (1990: 67).

President Bush invoked the concepts of good versus evil and us versus them when he provided an initial reason for the attack: “Our very freedom came under attack. ... America was targeted for attack because we’re the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in the world ... thousands of lives were suddenly ended by evil, despicable acts of terror” (Merskin, 2005: 376). He noted that, harbouring issues of stereotyping: “Today, our nation saw evil” and “the search is underway for those who are behind these evil acts.” (376). Faludi detailed that this rhetoric has occurred across even the early days of American history (the Puritan era) and how:

We perceive our country as inviolable

[…] and yet, our foundational drama as a society was apposite, a profound

exposure to just such assaults […] by dark-skinned, non-Christian combatants

under the flag of no recognised nation, complying with no accepted Western

rules of engagement and subscribing to an alien culture, who attacked white

America on its soil and against civilian targets. September 11 was aimed at our

cultural solar plexus precisely because it was an ‘unthinkable’ occurrence for

a nation that once could think of little else.

2007: 376

Once again, I liken this to

the 9/11 reactions, how ‘dread and fear regained prominence’ through the

dehumanisation of Muslims and ‘became politically instrumental tools for a

messianic Bush administration’ (Thompson, 2007: 17). Everything beyond the

family in The Witch is a symbol of otherness. Even the woodland is a

classified ‘other’ for these narratives. William assures his eldest son Caleb

(Harvey Scrimshaw) that they will “conquer this wilderness”. This rhetoric from William equates

to Bush’s propaganda against the Islamic ‘evil doers’ that inflicted damage on

American soil. It is a rhetoric that includes only Caleb and deliberately excludes

the womenfolk. But as stated earlier, 9/11 was no

‘victorious experience’ and the triumphant narratives conceived from this

rhetoric have since been demystified by authors and media scholars for the

propaganda that implemented a new captivity narrative that alienates any

outside the Western, Christian, Caucasian male group.

Father William’s flimsy masculinity bears

comparison to the promotion of “American chivalry” (2007, 65-89). All over the

country, ‘manly man’ dominated the advertisement, stretching from fictional

superheroes to even influential politicians in Bush’s cabinet, with their

bodies and faces edited in magazines to make them look like superheroes. Faludi notes

how:

Bush [featured] as a flinty cowboy in

chief […] and assigned all the president’s men superhero monikers: Dick Cheney

was ‘The Rock’, John Ashcroft ‘The Heat’ and Tom Ridge ‘The Protector’ […]

Rumsfeld had ‘gone to the mat with the al-Qaeda, displaying the same

matter-of-fact, oddly reassuring ruthlessness

2007:

48

The magazine’s editor-in-chief,

Graydon Carter, provided an answer to this imagery tsunami: “It’s not strength

but images of strength that matter in the 21st-century war” (Faludi, 2007: 48).

Caleb is employed into William’s fustian, expected to hunt and provide despite

being barely pubescent. He becomes lost in the forest on his first solo hunt,

barely holding his musket that equates to his size and appears engulfed by the

low-camera angles that encapsulate the branches and tree trunks towering over

him.

Conclusively, all this serves to

divert the narratives of not just the Puritan era but the media following 9/11,

an age-old tale reissued into society as the dominant language, about helpless

or rebellious women, savagery non-Christian groups and manly heroes. Western

society may have evolved from the oral medium of 14th-17th

Century Puritan civilisation to the printed/connected of the 21st,

yet the demeanour toward women, as well as other groups, remains practically the

same. We seem to return to the narratives that acquiesce women to restrictive

roles of submission or vilification. Their progressive independence was blamed

for the attacks.

What this article has aimed to display is that the stereotype of the witch and the captive narratives

“continues to loom large as an enemy of righteousness in conservative

evangelical rhetoric” (Zwissler: 20). What lies at the heart of this, as

authors like Thompson and Faludi have found, is a historical anomaly unique to

the American experience: the nation that in recent memory has been least

vulnerable to domestic attack was forged in traumatizing assaults by non-white

‘savages’ on their classification of society. That humiliation lies concealed

under a myth of Puritan captivity narratives of New England, the infant

America, that demonstrate a conflict and feeling of othering toward those

contradicting Puritan doctrine. It is these same narratives that saw the nation

return to these platitudes, in gender as much as race and faith, after the

foundations of their civil liberties were desecrated in the 2001 act of

terrorism that shook them to their core.

This could explain how the witch has evolved from a symbol of monstrosity to a representative of misogyny’s long history and of a feminine power that exists without the patriarchy. The phrase We Are The Grandaughters Of The Witches You Couldn’t Burn (Tish Thawer, 2015) is now a commonly seen slogan at feminist protests, as seen in the 2016 marches. As Toon stated, we turned our rage, fear and sadness into collective action that will hopefully bring about the new legislation (www.penguin.co.uk, 2021). This is similar to Cohen’s conclusion of Thomasin’s embrace of the witch coven: “She chooses to be a witch, the most reviled manifestation of womanhood – and she’s all the better for it” (March 17, 2016). But is this such a tale of empowerment or is this one of caution should these narratives continue to be endorsed? Jess Joho inquires “How can Thomasin’s story be of female empowerment when, as the final scenes imply, she chooses Satan because she has no other choice?” (February 23, 2016). Therefore, the author does not believe the film encourages women oppressed by these dogmas to embrace their ‘inner witch’. Rather, it is a plea for a time in which we would not draw to these fictions that demonise any outside the white Christian male category, lest we see these unfortunate scenarios of disarray, disunity and an eventual fall to madness and darkness.

Comments

Post a Comment